Abstract

Background and Objective: Given the dual public health challenges of under-treated pain and opioid abuse, there is a need to reduce attractiveness of opioid analgesics to drug abusers. ALO-01 (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended-release capsules, indicated for treatment of chronic, moderate to severe pain, contain polymer-coated pellets of morphine, each with a core of sequestered naltrexone intended for release only upon tampering (crushing). The purpose of this study was to assess the pharmacodynamic effects (including drug-liking and euphoria) of whole and crushed ALO-01 versus morphine sulfate solution (MSS) and placebo.

Methods: This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, triple-dummy, four-way crossover study carried out at a clinical research centre. Participants were experienced non-dependent opioid users. Subjects were given either two ALO-01 60 mg capsules, crushed pellets from two ALO-01 60 mg capsules, MSS 120 mg or placebo; there was a 14- to 21-day washout between treatments. The primary endpoints were drug-liking visual analogue scale score, scores on items from the Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI) and Cole/ARCI scales characterizing abuse potential and euphoria, and pupil diameter as measured by pupillometry.

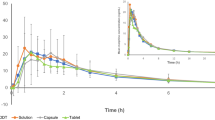

Results: Morphine plasma concentrations were similar after ALO-01 crushed and MSS, with a median time to reach maximum plasma concentration (tmax) of 1.1 and 1.2 hours, respectively; the plasma naltrexone median tmax was 1.1 hours after ALO-01 crushed. By comparison, the median tmax for morphine with ALO-01 whole was 8.1 hours. The maximum effect (Emax) of MSS was significantly greater than placebo on pupillometry and the subjective measures (all p < 0.001). ALO-01 whole and crushed produced lower Emax values and flatter effect-time profiles for subjective measures and caused less pupillary constriction than MSS.

Conclusions: The results of this study demonstrated that ALO-01, whether taken orally whole as intended or tampered with by crushing and taken orally, had reduced desirability compared with MSS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Pain Society. Pain control in the primary care setting. Glenview (IL): American Pain Society, 2006: 1–62

Woolf CJ, Hashmi M. Use and abuse of opioid analgesics: potential methods to prevent and deter non-medical consumption of prescription opioids. Curr Opin Invest Drugs 2004; 5(1): 61–6

World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care: report of a WHO expert committee [World Health Organization Technical Report Series, 804]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1990: 1–75

Kuehn BM. Opioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA 2007; 297(3): 249–51

Katz NP, Adams EH, Chilcoat H, et al. Challenges in the development of prescription opioid abuse-deterrent formulations. Clin J Pain 2007; 23(8): 648–60

Wilson JF. Strategies to stop abuse of prescribed opioid drugs. Ann Intern Med 2007; 146(12): 897–900

Katz NP, Adams EH, Benneyan JC, et al. Foundations of opioid risk management. Clin J Pain 2007; 23: 103–18

Crabtree BL. Review of naltrexone, a long-acting opiate antagonist. Clin Pharm 1984; 3: 273–80

Gonzalez J, Brogden RN. Naltrexone: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy in the management of opioid dependence. Drugs 1988; 35: 192–213

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Naltrexone for the management of opioid dependence. January 2007 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nice.org.uk/TA115 [Accessed 2009 May 27]

Katz N, Sun S, Johnson F, et al. ALO-01 (morphine sulfate and naltrexone hydrochloride) extended-release capsules in the treatment of chronic pain of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety. J Pain. In press

Balster RL, Bigelow GE. Guidelines and methodological reviews concerning drug abuse liability assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 70: S13–40

Jasinski DR. Assessment of the abuse potentiality of morphine like drugs (methods used in man). In: Martin WR, editor. Drug addiction. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1977: 197–258

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, et al. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1971 Mar–Apr; 12(2): 245–58

Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, Ator NA. Principles of initial experimental drug abuse liability assessment in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003; 70: S41–54

Cole JO, Orzack MH, Beake B, et al. Assessment of the abuse liability of buspirone in recreational sedative users. J Clin Psychiatry 1982; 43(12 Pt 2): 69–75

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: bioavailability and bioequivalence studies for orally administered drug products — general considerations. k-ville, MD: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; 2003

Knaggs RD, Crighton IM, Cobby TF, et al. The pupillary effects of intravenous morphine, codeine, and tramadol in volunteers. Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 108–12

Johnson F, Jones JB, Stauffer J. Relative bioavailability of plasma naltrexone from crushed ALO-01 (an investigational, abuse-deterrent, extended-release, morphine sulfate formulation with sequestered naltrexone) to a naltrexone oral solution [abstract 236]. J Pain 2008; 9(4 Suppl. 2): 35

Wright C, Kramer ED, Zalman M-A, et al. Risk identification, risk assessment, and risk management of abusable drug formulations. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006; 83(Suppl. 1): S68–76

Webster L, Jones JB, Johnson F, et al. Relative drug-liking/euphoria effects of intravenous morphine alone and in combination with naltrexone in recreational opioid users [abstract no. 2993]. International Association for the Study of Pain 12th World Congress on Pain; 2008 Aug 17–22; Glasgow, Scotland

Jones JB, Katz N, Fox L, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of ALO-01 (morphine sulfate extended-release with sequestered naltrexone hydrochloride) capsules in patients with chronic moderate-to-severe pain from osteoarthritis of the hip or knee [poster 238]. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: e97

Webster L, Brewer RP, Sekora D, et al. Long-term safety of ALO-01 (morphine sulfate extended-release with sequestered naltrexone hydrochloride) capsules in patients with chronic, moderate to severe, non-malignant pain [abstract 5]. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2008; 32: 5

Stanos S. Appropriate use of opioid analgesics in chronic pain. J Fam Pract 2007; 56(2 Suppl. Pain): 23–32

Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med 2008; 9: 444–59

Acknowledgements

This study and writing and editorial support for the manuscript were funded by King Pharmaceuticals®, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ, USA. Employee-authors from the study sponsor provided input into study design, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors of this article are current or former employees of the funding source (Joseph Stauffer, Beatrice Setnik, Franklin Johnson) or clinical research site (Marta Sokolowska, Myroslava Romach, Edward Sellers, Beatrice Setnik). Joseph Stauffer has previously owned stock in Alpharma Pharmaceuticals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of King Pharmaceuticals®, Inc., and has a patent pending with Alpharma Pharmaceuticals LLC. Beatrice Setnik has stock options in King Pharmaceuticals®, Inc. Franklin Johnson held stock in Alpharma Pharmaceuticals LLC and is a co-inventor of the EMBEDA™ technology. Edward Sellers, Marta Sokolowska and Myroslava Romach have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Joseph Stauffer and Franklin Johnson were responsible for the study design, analysis and interpretation of data, and planning, critical review and approval of manuscript drafts. Marta Sokolowska, Beatrice Setnik, Myroslava Romach (chief investigator) and Edward Sellers (chief scientific advisor) were responsible for protocol development and implementation, study assessments, data entry and transfer, analyses and interpretation of data, writing the clinical study report and critical review of outlines and manuscript drafts. All authors had full access to all data, including statistical reports and tables, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Beatrice Setnik is guarantor.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the scientific contribution of Dr James B. Jones to this project. Writing and editorial support for this manuscript was provided by Innovex Medical Communications, Parsippany, NJ, USA; however, the context and text are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/11533600-000000000-00000.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stauffer, J., Setnik, B., Sokolowska, M. et al. Subjective Effects and Safety of Whole and Tampered Morphine Sulfate and Naltrexone Hydrochloride (ALO-01) Extended-Release Capsules versus Morphine Solution and Placebo in Experienced Non-Dependent Opioid Users. Clin. Drug Investig. 29, 777–790 (2009). https://doi.org/10.2165/11530800-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11530800-000000000-00000